The Ultimate Guide To Online Beat Licensing

The Ultimate Guide To Online Beat Licensing

The Ultimate Guide To Online Beat Licensing

The Ultimate Guide To Online Beat Licensing

What once started with a few hundred producers on sites like Soundclick and MySpace has grown into a huge music-licensing industry led by platforms like BeatStars, Airbit, and Soundee.

Today, music production is easier than ever. Many people can now create a website to sell beats. However, beat licensing remains a serious business.

In this guide, we'll explain beat licensing and focus on the differences between Exclusive and Non-Exclusive Licenses. This information is useful for both artists buying beat licenses and producers selling them.

Sit back and relax! ☕️ By the end of this guide, you’ll know everything you need about online beat licensing.

Part 1: Beat Licensing Explained

Beat licensing is simple to understand. A producer creates a beat and uploads it to their online store. Artists can then buy these beats and use them for their songs.

When an artist buys a beat, they get a license agreement from the producer. This document grants the artist specific rights to create and distribute a song using that beat.

The license agreement serves as legal proof that the producer has given permission to use the beat.

A common misunderstanding is when artists ask producers for free beats. Even if a producer sends a free beat, it's essentially useless without a license agreement, as there's no legal permission to use it.

It's important to understand that when we talk about "buying beats" and "selling beats," what we're really dealing with is the license agreement, not just the beat itself.

Non-Exclusive Beat Licensing

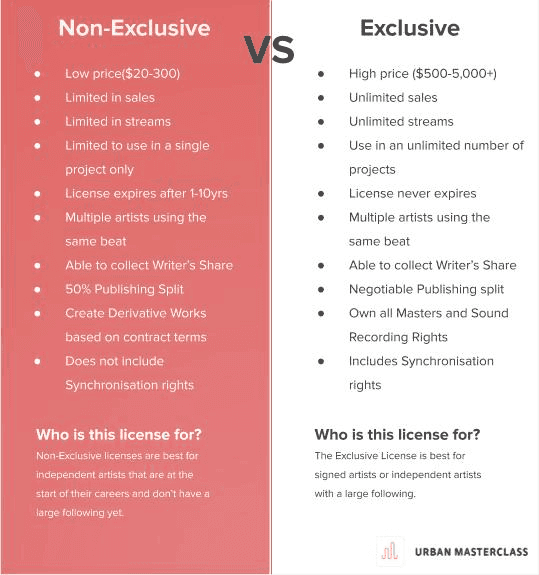

Non-exclusive licensing, or "leasing," is the most common form of beat licensing. For $20-$300, you can buy a non-exclusive license and use the beat to release a song on platforms like iTunes, Spotify, or Apple Music, make a music video for YouTube, and even earn money from it! 💰

These licenses are available directly from the producer’s online store. You can purchase them instantly without needing to inquire first.

Typically, the license agreement is auto-generated and includes the buyer’s name, address, timestamp (Effective Date), user rights, and the producer’s information.

A non-exclusive license allows the artist to use the beat to create and distribute their own song. However, the producer retains copyright ownership, and the artist must follow the terms specified in the license agreement.

The Limitations of Non-Exclusive Licenses

Non-exclusive licenses often come with limits on sales, plays, streams, or views. For instance, a license might allow only up to 50,000 streams on Spotify or 100,000 views on YouTube.

Additionally, non-exclusive licenses have an expiration date, typically lasting between 1-10 years. Once this period ends, you need to renew the license, which means buying a new one.

You also need to renew the license if you reach the maximum number of streams or plays before the expiration date.

Since these licenses are non-exclusive, the same beat can be licensed to many different artists. This means multiple artists could be using the same beat for their songs under similar terms.

Whether this is an issue depends on the artist's stage. Beginners might find a non-exclusive license suitable, while more established artists might prefer an exclusive license for unique rights.

The different types of Non-Exclusive Licenses

Most producers offer various non-exclusive licensing options. For example, I offer MP3, WAV, Premium, and Unlimited licenses.

Each option comes with its own set of user rights, which are often displayed in a table format.

Generally, the more expensive the license, the more user rights you get. Higher-priced licenses also come with better quality audio files.

In my case, the Premium license is the most popular. It offers the best audio quality, includes tracked-out files of the beat, and provides good user rights.

Artists who need even more rights typically choose the highest tier, the Unlimited license, or go for an Exclusive license.

Exclusive Beat Licensing

Owning the Exclusive Rights to a beat means there are no limitations on how you can use it. This allows the artist to fully exploit the song.

There are no caps on the number of streams, plays, sales, or downloads, and the contract does not have an expiration date.

The song can be used in multiple projects, such as singles, albums, and music videos. In contrast, non-exclusive licenses usually limit use to a single project.

When an artist buys the exclusive rights to a beat that was previously licensed non-exclusively, they become the last person to purchase it. After the beat is sold exclusively, the producer cannot sell or license it to anyone else.

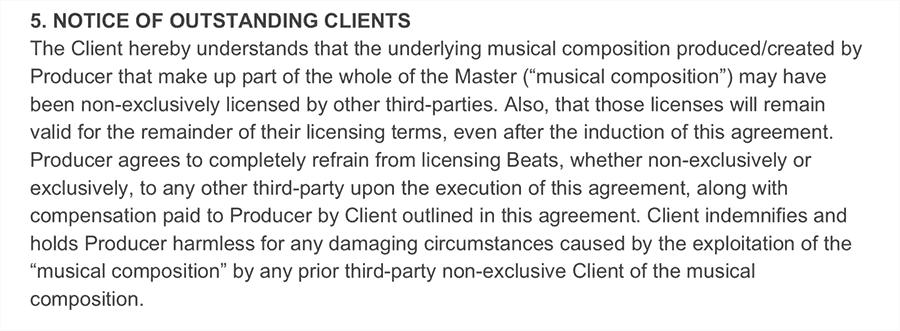

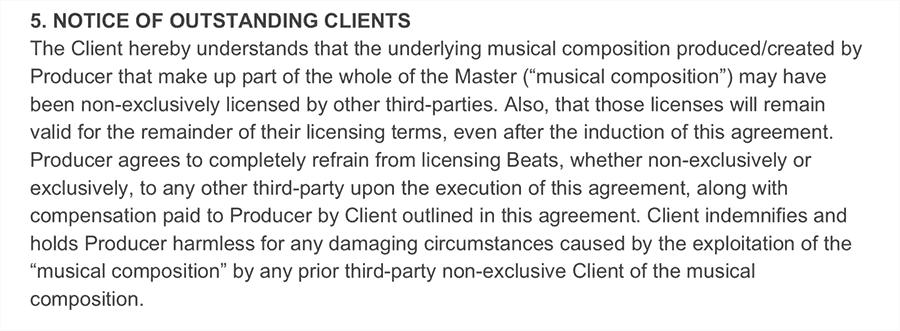

However, previous non-exclusive license holders are not affected. Exclusive contracts should include a "notice of outstanding clients" section to protect these previous licensees from any issues with the exclusive buyer.

These are the main differences between non-exclusive and exclusive licenses. But there's more to understand, especially regarding rights and royalties.

In the next sections of this guide, we'll delve deeper into Royalties, Publishing, and Copyright.

Two very different ways of selling Exclusive Rights

For many years, producers had different methods for selling exclusive rights. Recently, contracts have become more standardized, aligning with industry norms.

However, it’s important to understand the two main ways of selling exclusive rights:

Selling exclusive rights

Selling exclusive ownership

When selling exclusive rights, the producer remains the original author of the music and continues to collect writer's share and publishing rights.

When selling exclusive ownership, the producer transfers all rights, including authorship, copyright, and other interests, to the buyer. These deals, known as "work-for-hire," make the artist the legal author of the beat from that point on.

In the beat licensing industry, selling exclusive ownership is generally considered unethical and often violates copyright law. It’s best to reach an agreement where both the artist and producer are credited for their contributions legally, financially, and commercially.

Part 2: Everything you need to know about Royalties, Writers Share, and Publishing Rights

This part can be tricky because the music industry has many different deal structures. Don’t worry! 😉 By the end of this guide, you'll have a clear understanding.

Let's break it down step-by-step, focusing on online beat licensing.

First, we need to understand two types of royalties:

Mechanical Royalties

Performance Royalties

Mechanical Royalties

Mechanical royalties are earned when music is reproduced or distributed, either physically or digitally. This includes sales of CDs or vinyl, digital downloads (like on iTunes), and streams (like on Spotify).

Performance Royalties

Performance royalties are earned when a song is performed publicly. This includes music played on the radio, live performances, and streaming services.

Who gets the Mechanical Royalties?

Typically, artists get to keep 100% of the mechanical royalties if they pay for the license, whether it's non-exclusive or exclusive.

Nowadays, distribution services like TuneCore, CDBaby, or DistroKid pay these royalties directly to independent artists.

However, if an artist is signed to a label, the label usually collects the mechanical royalties and may choose to give a portion of them to the artist.

Advances against Mechanical Royalties in Exclusive Agreements

Usually, artists keep 100% of the mechanical royalties, but there’s an exception for exclusive agreements.

Some producers, including myself, request a small percentage of the mechanical royalties in these exclusive deals, typically between 1-10%.

This is known as "points" or "producer royalties."

In such cases, the price an artist pays for exclusive rights is considered an "advance against mechanical royalties." This advance is deducted from the net profit of the song before the producer gets their share. All costs to create the song, including the advance, are subtracted first.

Here’s an example to show you how this could potentially play out in a real-life situation.

Let’s say a producer sells exclusive rights to a beat for $1,000 as an advance against royalties. The producer's royalty rate is 3%.

The artist paid:

$1,000 for exclusive rights

$500 for studio time

$500 for getting the song mixed and mastered

Total expenses = $2,000

After 1 year, the song generated $10,000 in Mechanical Royalties!

The Net Profit: $10,000 - $2,000 expenses = $8,000 💰

The Producer’s Cut: 3% of $8,000 = $240

As an independent artist, generating $8,000 in mechanical royalties is significant, and only $240 goes to the producer.

Why an Advance against Royalties?

It might seem unnecessary, but there’s a reason why some producers, including myself, prefer selling exclusive rights with an advance against royalties.

A few years ago, I could sell exclusive rights for $2,000 to $10,000. (The Good Ol’ Days! 🤠)

Nowadays, it’s common to sell exclusive rights for less than $1,000. With the market becoming more competitive and saturated, prices have dropped, making it harder to secure high-value deals.

But what if the song becomes a huge hit?

Imagine a song generating millions of dollars, and you sold the exclusive rights for less than $1,000.

That doesn’t sound like a fair deal, does it?

An advance against royalties offers a solution. It acts as insurance for the producer in case the song blows up. The artist only has to pay the producer a small percentage (around 3%) once the song starts making significant revenue.

Who collects the Performance Royalties?

Performance royalties are collected and paid out by Performing Rights Organizations (PROs), like ASCAP or BMI in the US or PRS in the UK.

Each country has its own PRO, so check which one is yours)

These royalties are divided into two parts:

Songwriter Royalties (Writer’s Share)

Publishing Royalties

PROs collect both types of royalties and split them equally.

For every $1 earned in Performance Royalties:

$0.50 goes to Songwriter Royalties

$0.50 goes to Publishing Royalties.

The $0.50 in Songwriter Royalties is paid directly to the songwriters by the PRO.

The other $0.50 in Publishing Royalties is paid to a publishing company or publishing administrator (more about this later).

What are songwriter royalties?

First, let’s break down the Songwriter Royalties.

Songwriter royalties, also known as the “Writer’s Share,” are always paid to the credited songwriters. This portion cannot be sold through an exclusive license, except in a work-for-hire agreement.

In the world of online beat licensing, this is often misunderstood. According to copyright law, a producer is also considered a “songwriter.” 🤓

Songwriter royalties apply to anyone who has creative input in a song, including producers, lyricists, and sometimes even engineers.

Typically, non-exclusive beat licenses allocate 50% to publishing and 50% to the writer’s share. This is usually non-negotiable because the music (created by the producer) is considered half of the song, with the lyrics being the other half. If multiple songwriters contribute to the lyrics, they share that 50%.

Example Non-Exclusive beat licenses:

50% Producer

25% Writer 1

25% Writer 2

In exclusive rights deals, the split between all creators can be negotiated based on the price and the producer’s flexibility. While I generally stick to my 50%, some producers might agree to different splits.

Example Exclusive Licenses:

30% Producer

35% Writer 1

35% Writer 2

What are Publishing Royalties?

Unlike songwriter royalties, publishing royalties can be assigned to publishing companies. Most independent artists and producers don’t have a publishing deal, so they need to collect these royalties themselves.

A lot of money often goes unclaimed here. If you’re an independent artist or producer who is only signed up with a PRO and not with a publishing administrator, you might be missing out on half of your earnings.

For online beat licensing—whether exclusive or non-exclusive—the publishing share is usually equal to the writer's share.

So, 50% of the writer's share equals 50% of the publishing share.

Part 3: The Copyright Situation...Who owns what?

Copyright can be a complex topic, and there's more to it than I can cover here. For a deeper understanding, I recommend looking into Copyright Law online or consulting an attorney.

For now, I'll focus on copyright as it relates to licensing beats online. We’ll break down a song to identify its creators and copyright holders, making it clear who owns what.

Performing Arts Copyright (PA-Copyright)

Imagine you’re an artist searching for beats on YouTube. You find one you like, go to the producer's website, buy a license, write lyrics, create a song, and distribute it through CDBaby, TuneCore or DistroKid.

Your song has two copyrighted elements:

The Music

The Lyrics

The producer owns the copyright to the music, and you own the copyright to the lyrics.

Whether you’ve bought an exclusive or non-exclusive license, the producer always owns the music copyright, and you own the lyrics copyright (unless someone else wrote the lyrics).

This is known as Performing Arts Copyright (PA-Copyright).

Note: Many people think you must register your music or lyrics with the U.S. Copyright Office. In reality, as soon as you write something, make a beat, or save a demo, it’s copyrighted. Registering with the U.S. Copyright Office has benefits, but not doing so doesn’t mean you lose ownership of your creation.

Sound Recording Copyright (SR-Copyright)

Let’s go back to the song you made with the producer. Legally, this finished song is often called the “Master” or “Sound Recording.”

Understanding the difference between an exclusive and non-exclusive license is crucial here.

As an artist buying beats from a producer:

Exclusive License: You own the master and sound recording rights.

Non-Exclusive License: You do not own the master and sound recording rights.

With an exclusive license, the master rights are transferred to you, the artist, making the song your sole property without any claims from the producer. However, the producer still retains the right to claim copyright for the underlying musical composition (PA-Copyright), as they are the original creator of the music.

With a non-exclusive license, you do not own the master or sound recording rights. You are licensed to use the beat and commercially exploit the song under the terms of the non-exclusive agreement. However, you do own the PA-Copyright for the lyrics.

In this case, what you’ve created is called a Derivative Work.

What’s a Derivative Work?

In beat licensing, a derivative work is created when someone combines an original copyrighted work (the beat) with their own original work (the lyrics).

Derivative works are very common in the music industry and you probably come across them on a daily basis.

Examples are:

Remixes

Translations (A Spanish version of an English song)

Parodies

Movies based on books (Harry Potter)

These are all "new versions" created using preexisting copyrighted material.

In beat licensing, a non-exclusive agreement allows an artist to create such a "new version" using the producer's copyrighted material. Only the owner of the original composition (the producer) can authorize a derivative work.

When you license a beat non-exclusively, you are specifically given the right to create a derivative work.

Beats that contain third-party samples

Up until now, things have been pretty straightforward. But this next part is crucial, so please pay close attention.

Many producers mistakenly believe that when they sell beats with samples, the responsibility for clearing the sample falls on the artists who license the beat.

This is completely wrong!

It's a myth and couldn't be further from the truth. 🤦🏻♂️

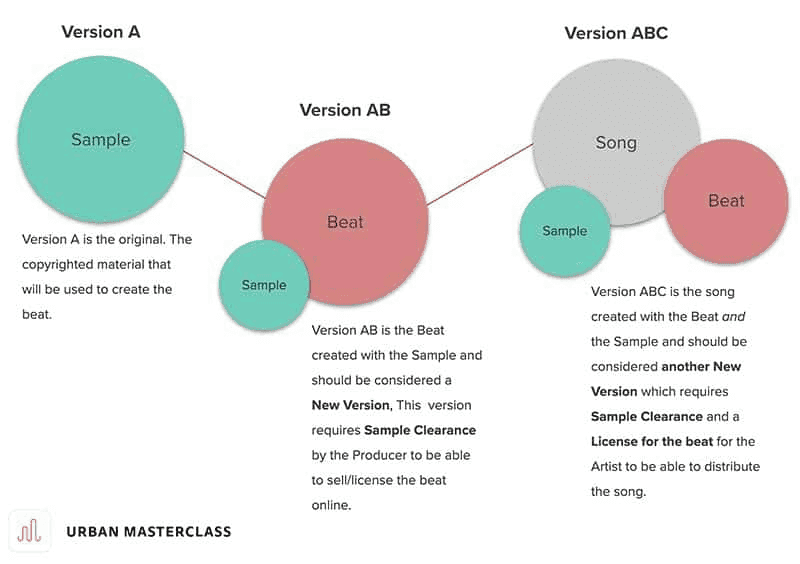

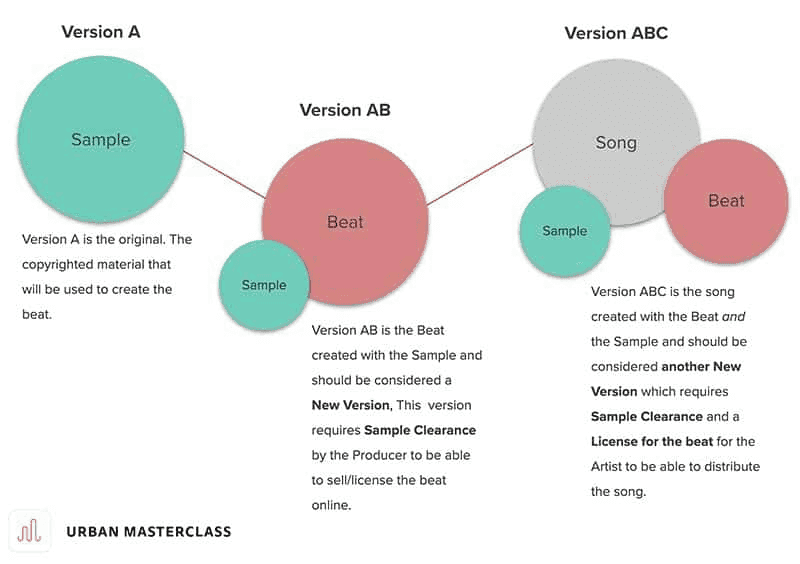

Take a look at the image below for context:

In the image, there are two different versions derived from the original sample: Version AB and Version ABC.

Since both versions are new works containing the original sample, clearing the sample for Version AB does not cover Version ABC.

Both the producer and the artist must clear the original sample. This is because there are three different copyright owners involved in this scenario.

Clearing the original sample is essential.

This process becomes even more complicated when multiple artists license the same beat and create their own songs from it. Over time, there could be many different versions derived from the same beat.

This is why I avoid using samples altogether. 😊

Exclusive or Non-Exclusive, what is best for you?

We've covered the differences between non-exclusive and exclusive licenses. But as an artist, you might still wonder which option is best for you.

While an exclusive license is generally better in many ways, it’s not necessary for everyone. In fact, most artists do better with a non-exclusive license.

Here’s what you should consider about your current situation:

How many followers and fans do you have?

How many songs have you released so far?

What’s your average number of plays or streams across all platforms?

How big is your marketing budget?

Are you receiving financial support from a label or publisher?

Ask yourself: What’s the best option for the artist you are TODAY?

Most artists aren’t ready to buy exclusive rights yet, and that’s perfectly okay. If you’re a new artist working on a mixtape or your first album, it doesn’t make sense to spend a lot on exclusive rights when you’re not sure if the record will be a hit.

A smarter investment would be to get a higher-tier non-exclusive license, preferably an Unlimited License. This way, you can spend less, buy more licenses, release more music, and gradually build your fanbase until you’re ready for the next step.

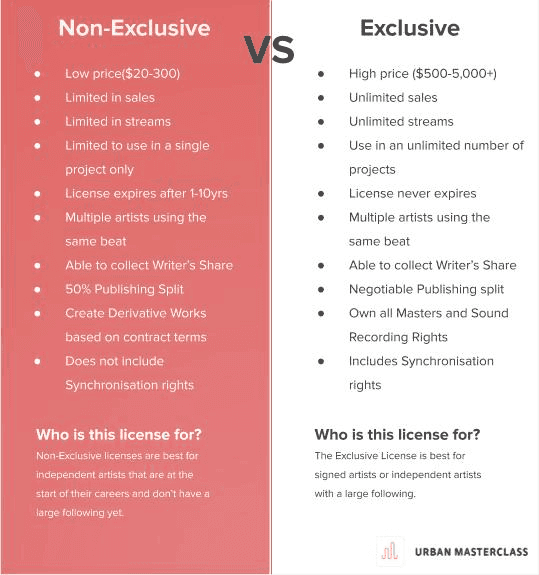

A summary of the differences between Exclusive and Non-Exclusive Licenses

Check out the image below for a summary and comparison of non-exclusive and exclusive beat licensing. Remember, the 'Sales' and 'Streams' limit doesn’t apply to Unlimited licenses.

Part 4: FAQ About Beat Licensing

We regularly update this guide to answer the most frequently asked questions about beat licensing.

I want to license a beat that the producer already sold. Can I reach out to the exclusive buyer to get a license?

No, that's not possible. Some artists mistakenly think they can contact the buyer to get a license, but exclusive contracts prohibit reselling or licensing the beat in its original form unless it’s overlaid with lyrics.

Doing so would breach the exclusive agreement.

I bought a non-exclusive license for a beat, but now someone else bought it exclusively. What happens to my song?

Nothing changes for you! Your license remains valid for the duration of the agreement or until you reach the maximum number of streams or plays specified in your license.

Your license agreement includes an "Effective Date" (when you bought the license) and an "Expiration Date" (either a set date or a period like five years). The exclusive contract with the new buyer should include a "notice of outstanding clients," which protects your rights.

My non-exclusive license is reaching its streaming limit, but I can't buy a new license because the beat is sold exclusively. Do I have to take my song down?

Yes, if you reach the streaming limits and can't extend the license, you will have to take the song down.

This is why Unlimited Licenses are a great option—they have no streaming cap, avoiding situations like this, even though they are more expensive.

What once started with a few hundred producers on sites like Soundclick and MySpace has grown into a huge music-licensing industry led by platforms like BeatStars, Airbit, and Soundee.

Today, music production is easier than ever. Many people can now create a website to sell beats. However, beat licensing remains a serious business.

In this guide, we'll explain beat licensing and focus on the differences between Exclusive and Non-Exclusive Licenses. This information is useful for both artists buying beat licenses and producers selling them.

Sit back and relax! ☕️ By the end of this guide, you’ll know everything you need about online beat licensing.

Part 1: Beat Licensing Explained

Beat licensing is simple to understand. A producer creates a beat and uploads it to their online store. Artists can then buy these beats and use them for their songs.

When an artist buys a beat, they get a license agreement from the producer. This document grants the artist specific rights to create and distribute a song using that beat.

The license agreement serves as legal proof that the producer has given permission to use the beat.

A common misunderstanding is when artists ask producers for free beats. Even if a producer sends a free beat, it's essentially useless without a license agreement, as there's no legal permission to use it.

It's important to understand that when we talk about "buying beats" and "selling beats," what we're really dealing with is the license agreement, not just the beat itself.

Non-Exclusive Beat Licensing

Non-exclusive licensing, or "leasing," is the most common form of beat licensing. For $20-$300, you can buy a non-exclusive license and use the beat to release a song on platforms like iTunes, Spotify, or Apple Music, make a music video for YouTube, and even earn money from it! 💰

These licenses are available directly from the producer’s online store. You can purchase them instantly without needing to inquire first.

Typically, the license agreement is auto-generated and includes the buyer’s name, address, timestamp (Effective Date), user rights, and the producer’s information.

A non-exclusive license allows the artist to use the beat to create and distribute their own song. However, the producer retains copyright ownership, and the artist must follow the terms specified in the license agreement.

The Limitations of Non-Exclusive Licenses

Non-exclusive licenses often come with limits on sales, plays, streams, or views. For instance, a license might allow only up to 50,000 streams on Spotify or 100,000 views on YouTube.

Additionally, non-exclusive licenses have an expiration date, typically lasting between 1-10 years. Once this period ends, you need to renew the license, which means buying a new one.

You also need to renew the license if you reach the maximum number of streams or plays before the expiration date.

Since these licenses are non-exclusive, the same beat can be licensed to many different artists. This means multiple artists could be using the same beat for their songs under similar terms.

Whether this is an issue depends on the artist's stage. Beginners might find a non-exclusive license suitable, while more established artists might prefer an exclusive license for unique rights.

The different types of Non-Exclusive Licenses

Most producers offer various non-exclusive licensing options. For example, I offer MP3, WAV, Premium, and Unlimited licenses.

Each option comes with its own set of user rights, which are often displayed in a table format.

Generally, the more expensive the license, the more user rights you get. Higher-priced licenses also come with better quality audio files.

In my case, the Premium license is the most popular. It offers the best audio quality, includes tracked-out files of the beat, and provides good user rights.

Artists who need even more rights typically choose the highest tier, the Unlimited license, or go for an Exclusive license.

Exclusive Beat Licensing

Owning the Exclusive Rights to a beat means there are no limitations on how you can use it. This allows the artist to fully exploit the song.

There are no caps on the number of streams, plays, sales, or downloads, and the contract does not have an expiration date.

The song can be used in multiple projects, such as singles, albums, and music videos. In contrast, non-exclusive licenses usually limit use to a single project.

When an artist buys the exclusive rights to a beat that was previously licensed non-exclusively, they become the last person to purchase it. After the beat is sold exclusively, the producer cannot sell or license it to anyone else.

However, previous non-exclusive license holders are not affected. Exclusive contracts should include a "notice of outstanding clients" section to protect these previous licensees from any issues with the exclusive buyer.

These are the main differences between non-exclusive and exclusive licenses. But there's more to understand, especially regarding rights and royalties.

In the next sections of this guide, we'll delve deeper into Royalties, Publishing, and Copyright.

Two very different ways of selling Exclusive Rights

For many years, producers had different methods for selling exclusive rights. Recently, contracts have become more standardized, aligning with industry norms.

However, it’s important to understand the two main ways of selling exclusive rights:

Selling exclusive rights

Selling exclusive ownership

When selling exclusive rights, the producer remains the original author of the music and continues to collect writer's share and publishing rights.

When selling exclusive ownership, the producer transfers all rights, including authorship, copyright, and other interests, to the buyer. These deals, known as "work-for-hire," make the artist the legal author of the beat from that point on.

In the beat licensing industry, selling exclusive ownership is generally considered unethical and often violates copyright law. It’s best to reach an agreement where both the artist and producer are credited for their contributions legally, financially, and commercially.

Part 2: Everything you need to know about Royalties, Writers Share, and Publishing Rights

This part can be tricky because the music industry has many different deal structures. Don’t worry! 😉 By the end of this guide, you'll have a clear understanding.

Let's break it down step-by-step, focusing on online beat licensing.

First, we need to understand two types of royalties:

Mechanical Royalties

Performance Royalties

Mechanical Royalties

Mechanical royalties are earned when music is reproduced or distributed, either physically or digitally. This includes sales of CDs or vinyl, digital downloads (like on iTunes), and streams (like on Spotify).

Performance Royalties

Performance royalties are earned when a song is performed publicly. This includes music played on the radio, live performances, and streaming services.

Who gets the Mechanical Royalties?

Typically, artists get to keep 100% of the mechanical royalties if they pay for the license, whether it's non-exclusive or exclusive.

Nowadays, distribution services like TuneCore, CDBaby, or DistroKid pay these royalties directly to independent artists.

However, if an artist is signed to a label, the label usually collects the mechanical royalties and may choose to give a portion of them to the artist.

Advances against Mechanical Royalties in Exclusive Agreements

Usually, artists keep 100% of the mechanical royalties, but there’s an exception for exclusive agreements.

Some producers, including myself, request a small percentage of the mechanical royalties in these exclusive deals, typically between 1-10%.

This is known as "points" or "producer royalties."

In such cases, the price an artist pays for exclusive rights is considered an "advance against mechanical royalties." This advance is deducted from the net profit of the song before the producer gets their share. All costs to create the song, including the advance, are subtracted first.

Here’s an example to show you how this could potentially play out in a real-life situation.

Let’s say a producer sells exclusive rights to a beat for $1,000 as an advance against royalties. The producer's royalty rate is 3%.

The artist paid:

$1,000 for exclusive rights

$500 for studio time

$500 for getting the song mixed and mastered

Total expenses = $2,000

After 1 year, the song generated $10,000 in Mechanical Royalties!

The Net Profit: $10,000 - $2,000 expenses = $8,000 💰

The Producer’s Cut: 3% of $8,000 = $240

As an independent artist, generating $8,000 in mechanical royalties is significant, and only $240 goes to the producer.

Why an Advance against Royalties?

It might seem unnecessary, but there’s a reason why some producers, including myself, prefer selling exclusive rights with an advance against royalties.

A few years ago, I could sell exclusive rights for $2,000 to $10,000. (The Good Ol’ Days! 🤠)

Nowadays, it’s common to sell exclusive rights for less than $1,000. With the market becoming more competitive and saturated, prices have dropped, making it harder to secure high-value deals.

But what if the song becomes a huge hit?

Imagine a song generating millions of dollars, and you sold the exclusive rights for less than $1,000.

That doesn’t sound like a fair deal, does it?

An advance against royalties offers a solution. It acts as insurance for the producer in case the song blows up. The artist only has to pay the producer a small percentage (around 3%) once the song starts making significant revenue.

Who collects the Performance Royalties?

Performance royalties are collected and paid out by Performing Rights Organizations (PROs), like ASCAP or BMI in the US or PRS in the UK.

Each country has its own PRO, so check which one is yours)

These royalties are divided into two parts:

Songwriter Royalties (Writer’s Share)

Publishing Royalties

PROs collect both types of royalties and split them equally.

For every $1 earned in Performance Royalties:

$0.50 goes to Songwriter Royalties

$0.50 goes to Publishing Royalties.

The $0.50 in Songwriter Royalties is paid directly to the songwriters by the PRO.

The other $0.50 in Publishing Royalties is paid to a publishing company or publishing administrator (more about this later).

What are songwriter royalties?

First, let’s break down the Songwriter Royalties.

Songwriter royalties, also known as the “Writer’s Share,” are always paid to the credited songwriters. This portion cannot be sold through an exclusive license, except in a work-for-hire agreement.

In the world of online beat licensing, this is often misunderstood. According to copyright law, a producer is also considered a “songwriter.” 🤓

Songwriter royalties apply to anyone who has creative input in a song, including producers, lyricists, and sometimes even engineers.

Typically, non-exclusive beat licenses allocate 50% to publishing and 50% to the writer’s share. This is usually non-negotiable because the music (created by the producer) is considered half of the song, with the lyrics being the other half. If multiple songwriters contribute to the lyrics, they share that 50%.

Example Non-Exclusive beat licenses:

50% Producer

25% Writer 1

25% Writer 2

In exclusive rights deals, the split between all creators can be negotiated based on the price and the producer’s flexibility. While I generally stick to my 50%, some producers might agree to different splits.

Example Exclusive Licenses:

30% Producer

35% Writer 1

35% Writer 2

What are Publishing Royalties?

Unlike songwriter royalties, publishing royalties can be assigned to publishing companies. Most independent artists and producers don’t have a publishing deal, so they need to collect these royalties themselves.

A lot of money often goes unclaimed here. If you’re an independent artist or producer who is only signed up with a PRO and not with a publishing administrator, you might be missing out on half of your earnings.

For online beat licensing—whether exclusive or non-exclusive—the publishing share is usually equal to the writer's share.

So, 50% of the writer's share equals 50% of the publishing share.

Part 3: The Copyright Situation...Who owns what?

Copyright can be a complex topic, and there's more to it than I can cover here. For a deeper understanding, I recommend looking into Copyright Law online or consulting an attorney.

For now, I'll focus on copyright as it relates to licensing beats online. We’ll break down a song to identify its creators and copyright holders, making it clear who owns what.

Performing Arts Copyright (PA-Copyright)

Imagine you’re an artist searching for beats on YouTube. You find one you like, go to the producer's website, buy a license, write lyrics, create a song, and distribute it through CDBaby, TuneCore or DistroKid.

Your song has two copyrighted elements:

The Music

The Lyrics

The producer owns the copyright to the music, and you own the copyright to the lyrics.

Whether you’ve bought an exclusive or non-exclusive license, the producer always owns the music copyright, and you own the lyrics copyright (unless someone else wrote the lyrics).

This is known as Performing Arts Copyright (PA-Copyright).

Note: Many people think you must register your music or lyrics with the U.S. Copyright Office. In reality, as soon as you write something, make a beat, or save a demo, it’s copyrighted. Registering with the U.S. Copyright Office has benefits, but not doing so doesn’t mean you lose ownership of your creation.

Sound Recording Copyright (SR-Copyright)

Let’s go back to the song you made with the producer. Legally, this finished song is often called the “Master” or “Sound Recording.”

Understanding the difference between an exclusive and non-exclusive license is crucial here.

As an artist buying beats from a producer:

Exclusive License: You own the master and sound recording rights.

Non-Exclusive License: You do not own the master and sound recording rights.

With an exclusive license, the master rights are transferred to you, the artist, making the song your sole property without any claims from the producer. However, the producer still retains the right to claim copyright for the underlying musical composition (PA-Copyright), as they are the original creator of the music.

With a non-exclusive license, you do not own the master or sound recording rights. You are licensed to use the beat and commercially exploit the song under the terms of the non-exclusive agreement. However, you do own the PA-Copyright for the lyrics.

In this case, what you’ve created is called a Derivative Work.

What’s a Derivative Work?

In beat licensing, a derivative work is created when someone combines an original copyrighted work (the beat) with their own original work (the lyrics).

Derivative works are very common in the music industry and you probably come across them on a daily basis.

Examples are:

Remixes

Translations (A Spanish version of an English song)

Parodies

Movies based on books (Harry Potter)

These are all "new versions" created using preexisting copyrighted material.

In beat licensing, a non-exclusive agreement allows an artist to create such a "new version" using the producer's copyrighted material. Only the owner of the original composition (the producer) can authorize a derivative work.

When you license a beat non-exclusively, you are specifically given the right to create a derivative work.

Beats that contain third-party samples

Up until now, things have been pretty straightforward. But this next part is crucial, so please pay close attention.

Many producers mistakenly believe that when they sell beats with samples, the responsibility for clearing the sample falls on the artists who license the beat.

This is completely wrong!

It's a myth and couldn't be further from the truth. 🤦🏻♂️

Take a look at the image below for context:

In the image, there are two different versions derived from the original sample: Version AB and Version ABC.

Since both versions are new works containing the original sample, clearing the sample for Version AB does not cover Version ABC.

Both the producer and the artist must clear the original sample. This is because there are three different copyright owners involved in this scenario.

Clearing the original sample is essential.

This process becomes even more complicated when multiple artists license the same beat and create their own songs from it. Over time, there could be many different versions derived from the same beat.

This is why I avoid using samples altogether. 😊

Exclusive or Non-Exclusive, what is best for you?

We've covered the differences between non-exclusive and exclusive licenses. But as an artist, you might still wonder which option is best for you.

While an exclusive license is generally better in many ways, it’s not necessary for everyone. In fact, most artists do better with a non-exclusive license.

Here’s what you should consider about your current situation:

How many followers and fans do you have?

How many songs have you released so far?

What’s your average number of plays or streams across all platforms?

How big is your marketing budget?

Are you receiving financial support from a label or publisher?

Ask yourself: What’s the best option for the artist you are TODAY?

Most artists aren’t ready to buy exclusive rights yet, and that’s perfectly okay. If you’re a new artist working on a mixtape or your first album, it doesn’t make sense to spend a lot on exclusive rights when you’re not sure if the record will be a hit.

A smarter investment would be to get a higher-tier non-exclusive license, preferably an Unlimited License. This way, you can spend less, buy more licenses, release more music, and gradually build your fanbase until you’re ready for the next step.

A summary of the differences between Exclusive and Non-Exclusive Licenses

Check out the image below for a summary and comparison of non-exclusive and exclusive beat licensing. Remember, the 'Sales' and 'Streams' limit doesn’t apply to Unlimited licenses.

Part 4: FAQ About Beat Licensing

We regularly update this guide to answer the most frequently asked questions about beat licensing.

I want to license a beat that the producer already sold. Can I reach out to the exclusive buyer to get a license?

No, that's not possible. Some artists mistakenly think they can contact the buyer to get a license, but exclusive contracts prohibit reselling or licensing the beat in its original form unless it’s overlaid with lyrics.

Doing so would breach the exclusive agreement.

I bought a non-exclusive license for a beat, but now someone else bought it exclusively. What happens to my song?

Nothing changes for you! Your license remains valid for the duration of the agreement or until you reach the maximum number of streams or plays specified in your license.

Your license agreement includes an "Effective Date" (when you bought the license) and an "Expiration Date" (either a set date or a period like five years). The exclusive contract with the new buyer should include a "notice of outstanding clients," which protects your rights.

My non-exclusive license is reaching its streaming limit, but I can't buy a new license because the beat is sold exclusively. Do I have to take my song down?

Yes, if you reach the streaming limits and can't extend the license, you will have to take the song down.

This is why Unlimited Licenses are a great option—they have no streaming cap, avoiding situations like this, even though they are more expensive.